Word of

Coldwater's status traveled fast in the local caver grapevine. Neil Saylor of

the Minnesota Speleological Survey (MSS) took a fervent interest in Jagnow and

Barnett's caving exploits. With information he garnered from past trip

reports, the IGS Coldwater Study, and his extensive surface checking, he saw

three areas of exploration potential.

Saylor observed from his field checking excursions that he was unable to

follow the route of the water in the many sinkholes that drained land directly

above the cave. The existence of numerous domes that feed water into

mainstream Coldwater via unpushed upper leads caused him to postulate the

existence of an extensive upper level. A sinkhole plain east of Coldwater

drains a large surface area under which there was no known cave. That, coupled

with Barnett's report of crossing a drainage divide in an eastern downstream

side passage, raised the possibility in Saylor's mind of a parallel extension

to the main stream. Finally, the fact that most of the water in Coldwater

originates beyond the terminal upstream sump was indicative of more passage

upstream and beyond.

In early 1975, Saylor approached the landowner about the possibility of

cavers continuing to explore and map Coldwater Cave, emphasizing that the cave

still had potential. Ken Flatland was amenable to the idea and granted the MSS

access to the cave.

During that year Saylor led MSS cavers in a dual quest: pursuit of the

speculated upper level and penetration of the upstream sump. They made several

attempts to reach the upper lead in the Waterfall Dome, but were unsuccessful

in negotiating the climb. Ron Spong, taking advantage of low water levels,

braved the upstream siphon surfacing in a large breakdown room. He traversed

the room and encountered another sump. Since he was alone, he felt it prudent

to terminate his exploration.

After several unsuccessful and frustrating upstream trips, MSS cavers

elected to concentrate their efforts in the eastern side passages downstream

from the shaft. They explored the Monument Passage and mapped and connected

the Well Pipe and Cascade Creek Passages. With white faced trepidation they

reported on how suddenly the water rises in the Cascade Creek Passage in

response to rain. They also noted that the Monument Passage, the only

downstream passage that doesn't feed the mainstream, appears to direct water

away to some unknown destination.

Other cavers also became interested and were allowed access to Coldwater

Cave during 1975. Saylor played the classic suck in, casually dropping hints

about upper levels, parallel systems, and upstream borehole. This tactic

inspired Iowa Grotto members to do several reconnaissance trips to the cave,

and in November, Rock River Speleological Society (RRSS) became interested in

starting a grotto survey project. With Ken Flatland's blessing and Neil

Saylor's direction, the group opted to work the upstream section of the cave.

RRSS resurveyed sections of the mainstream from the shaft to the upstream

sump and pushed and mapped the Snake Passage. Accompanied by cavers from Iowa

Grotto, Wisconsin Speleological Society and Windy City Grotto, they surveyed

the Waterfall and Pete's Pipe Passages discovering that the two connected.

On some trips people noticed that they shared symptoms of indigestion,

headache, and breathlessness. At times carbide lamps burned "funny," and a few

trips were cut short because the participants felt bad physically. Doc Lewis

concluded that they probably suffered from the high C02/low 02 levels and

prescribed downstream trips or surface reconnaissance for those weekends when

the high levels were suspected.

In the spring of 1976, an upstream exploratory crew discovered a dome 150

ft from the Waterfall Dome containing what appeared to be a walking height

upper lead. Could this be Neil Saylor's upper level? In anticipation, it was

named Gateway Dome. Rock River cavers designed and built a climbing pole, and

in July of that year dragged it nearly 11/2 miles upstream to push to dome. To

everyone's disappointment the passage ended in unstable breakdown after a few

feet. Several more unsuccessful assaults were launched on the Waterfall Dome

and finally, in 1978, WSS cavers completed the climb, reporting a small

crawlway blocked by breakdown.

During the fall of 1976, RRSS members Tom Backer, Pete DeVries, Duke

Hopper, Dave Smith, and R.C. Schroeder made two trips beyond the first

upstream sump, emerging in the breakdown room that Spong of the MSS had

described. They surveyed through a low air section, popped out in a second big

room and mapped to another low air lead (The Tuna Sea). Schroeder cautiously

inched his way in a 3.5 inch air space water crawl to a cross joint beyond

which the passage appeared to sump. Total surveyed distance was 1100 ft.

The marginal air space encountered in the upstream sump along with

fluctuations in water level dependent on surface weather conditions made

passing the upstream sump a dangerous proposition. Because upstream potential

seemed so probable, cavers looked to the grim little tributaries feeding the

Waterfall Passage. They speculated, based on the Waterfall Pipe Passage link,

that a connection was possible between the Waterfall Passage and upstream

beyond the Tuna Sea. A core group of RRSS cavers (Bruce Coulter, Pat Kambesis,

Brad Olson and Mark Rohn) spent over a year conducting a systematic survey of

the west trending crawlways off the Waterfall Passage. They mapped hundreds of

feet of low, muddy passage, but found no bypass.

Their last hope lay in the Obstruction Passage, another sleazeway supreme

that blew lots of air but where exploration was stymied by a 4 foot long

flowstone blockade. There was a narrow space between the ceiling and the

obstruction which looked almost impossible for human penetration. Numerous

attempts and various methods were made to enlarge the window over the

blockade. Finally, small cavers, willing to remove their wetsuit tips,

squeezed through the "window" to the other side: bigger cavers, agreeable to

being bodily pushed/pulled, were stuffed through the hole. The several trips

that ensued found nearly 1000 ft of flat out belly crawl (with no end in

sight) and a wind that chilled them to the bone. One last major push was

attempted by Pat Kambesis and Philip Moss in the summer of 1980. They noted

the absence of air movement and suffered mild effects of high C02 levels.

Perhaps the entrance to the connection route beyond the Tuna Sea had silted

shut during the spring floods.

Cavers continued to push leads in the upstream domes with little success.

Passages at the top were either too small for human entry or were filled with

breakdown. In early 1979, RRSS made a final attempt on the upstream sump,

enlisting the help of a group of newly certified cave divers. The divers,

expecting Florida water conditions and worn out by the long trek to the

upstream lead, never made it to the Tuna Sea.

With interest and enthusiasm in upstream Coldwater at low ebb, the project

gradually shifted focus downstream. Coldwater project members resurveyed the

main passage from the entrance shaft to the downstream sump. Upstream cleanup

surveys alternated with downstream reconnaissance trips to the Cascade Creek,

Well Pipe, and Monument Passages. Mapping commenced in smaller downstream

leads and several domes near the entrance shaft received concentrated climbing

pole attention. The upstream sumps took low priority to the continued search

for the evasive upper level.

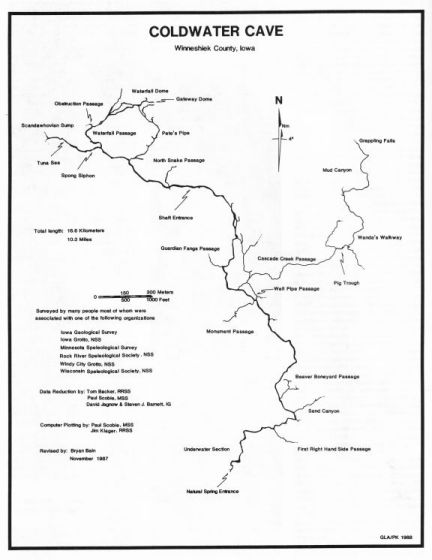

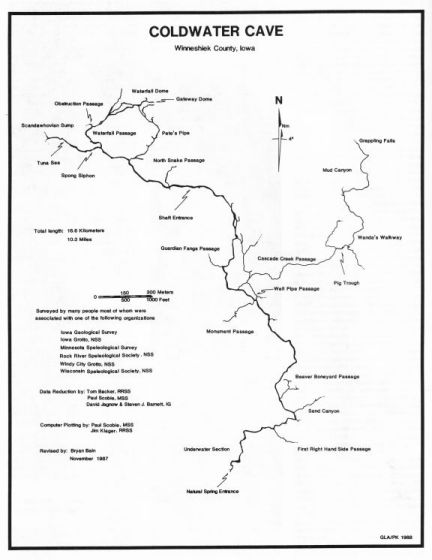

As of 1980, there were 7 miles of surveyed passage in Coldwater Cave with

additional known cave that wasn't on the map. In an effort to increase survey

footage, they concentrated on finishing off incomplete areas and rechecking

old leads.

Of particular interest was the Cascade Creek Passage where MSS cavers had

surveyed 3/4 of a mile and left some unchecked leads. The passage was

intriguing in that, during the winter, water flowing from it seemed to run a

little colder than the rest of the main stream. Water levels responded quickly

during floods and air flow was good. Subsequently, what started as a cleanup

survey turned into one of the most significant discoveries in Coldwater Cave,

fulfilling another Neil Saylor prediction and adding nearly 2 miles of passage

to the map.

Over a number of trips, Gary Engh, Barry Shuman, Cbuck Rex, John Moses,

Glenn Glasser and others explored and remapped the Cascade Passage. They

discovered bats in a cross joint off the main stream Cascade a first in

Coldwater Cave, and perhaps an indication of another entrance in that area. A

sleazy side passage before the bat cross joint was dubbed the Pig Trough, it

later proved to be an important area in this section of cave. As the survey

progressed in Pig Trough, cavers breached a drainage divide which broke into a

parallel drainage system named Wanda's Walkway. A downstream push found sumped

passage via a tangle of breakdown and deep water. The upstream route yielded a

series of domes and crawls which led to a junction room (the Roundhouse)

measuring 40 ft long, 25 ft wide, and 7 ft high. Five passages lead out of the

room like spokes from a hub.

Cavers pushed a north trending lead out of the Roundhouse to Mud Canyon,

600 ft of mushy meandering mudbank passage. As the group progressed upstream,

mud became less of a problem and passage decoration appeared, then increased

in density. Squeezing through a near choke of formations and traversing

another 300 ft, they discovered a large 80 to 90 ft high dome room. A

waterfall poured out from a walking height lead 10 ft up the wall.

Using some webbing, Gary Engh lassoed the lip and negotiated the tenuous

climb. Upon reaching the top he could see virgin passage. He could also see

that the webbing was marginally supported by a jumble of big, unstable

breakdown. Gary felt that the dangerous nature of the breakdown, coupled with

the insufficient webbing rig, made further progress too risky at that point.

In spite of the promising lead, the long, strenuous trip required to reach

this remote area proved to be a near endurance barrier for many cavers and

interest temporarily waned.

Like many long term caving endeavors, the Coldwater Project went through a

period of stagnation. Several good cavers left the area and interest and

motivation went into remission. In spite of this, people continued to meet and

go caving on the third weekend every month.

Continued Exploration in Wanda's Walkway and the Upstream

Sumps

Another trait of long-term caving projects is that a little new

blood is all that is needed to spark enthusiasm and renew activity. New cavers

to the project began working bring interest back with the help of some of the

remaining "old timers."

Mapping trips to the many small, miserable side passages slowly increased

total survey footage. Digging projects were initiated in Sand Canyon and

Monument Passage. New leads were noted and old ones were scrutinized with new

enthusiasm. In December of 1986 Dave and Sue Ecklund led a survey trip into

Guardian Fangs Passage, bringing the total surveyed footage to 10 miles; a

goal accomplished by the cumulative hard work of many cavers over the past 19

years.

Gary Engh, Larry Welch, and Bryan Bain returned to Wanda's Walkway in the

spring of 1987, equipped with a collapsible grappling hook and tossed it into

the upper level waterfall lead, which was subsequently called Grappling Falls.

Logistical problems postponed the ascent to a later trip on which Bain was

successful in reaching the upper lead and bypassing the unstable breakdown.

Big virgin passage led away from the top of the waterfall and over massive

breakdown for several hundred feet to the source of the water; a 4 ft wide by

2 ft high slot that moved plenty of air an excellent indication of more cave

passage and a push left for another trip.

Iowa Grotto cavers tried their luck at the Spong Siphon, making two

unsuccessful attempts in late 1985. Mike Nelson, undeterred by the results of

the previous trips, grew fascinated and then obsessed with what lay beyond the

upstream sumps. The low air space so characteristic of the area intimidated

most cavers and usually "wetted down" their interest after a first trip.

Nelson, who seems to thrive on ear crawls and intimate nose to ceiling

contact, has been the driving force in current upstream exploration.

At about the same time that interest was renewed in the upstream sumps,

Betty Wheeler, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, began

conducting a series of dye traces. Rhodamine dye, which was introduced on the

surface upstream from the Tuna Sea, rapidly found a way into the cave and

inspired another round of Tuna Sea fever.

The low water levels of January 1986 allowed Nelson to nose his way through

Spong Siphon to the first cross joint in the Tuna Sea and beyond R.C.

Schroeder's farthest point of penetration. He traversed approximately 300 ft

of 3 6 in air space through a series of cross joints and rooms to "Beyond the

Tuna Sea" After another 300 ft of virgin passage, he turned back. Excited and

doubly determined, he returned to the surface to instigate plans for a full

scale exploration and survey trip.

Two weeks later, he returned to the site with a group of seven Iowa Grotto

cavers. They pushed and mapped nearly 1000 feet of passage to Scandawhovian

Sumps and noted a pyramid-shaped side passage that also sumped. Spring rains

reinstated the normally high water levels and it was 11 months before the

water dropped enough to allow further exploration.

In early 1987, Nelson launched another trip upstream where he did a belayed

free dive reconnaissance of the Scandawhovian Sumps, finding going passage

beyond them. However, the big breakthrough came in June of 1987. Nelson,

accompanied by Minnesota cave diver Larry Laine, set out to push the

Scandawhovian Sumps. They negotiated 50 ft of low air/no air passage, donning

SCUBA gear in a cross joint and proceeded to another sump (Three Dive Sump).

As the name implies it took three attempts before they emerged in new

territory. The route forked farther upstream and they chose the north trending

lead.

A tight horizontal squeeze opened to a small room, then a hands and knees

water crawl, and finally stoop walking passage. Laine waited here while Nelson

continued to explore. Passage dimensions enlarged to walking size and he found

two large rooms, a breakdown area, and some promising leads. Realizing that

they were overdue on the surface, the two retraced their steps, pacing off

3000 ft of new passage.

A return trip in July included Mike Nelson, Dave and Sue Ecklund, Bill

Nelson, and Doug Schmeucker. The group mapped 450 ft in the south fork to the

"End Again Sump. " Mike probed the sump with his feet and found air on the

other side. However, a dive was not attempted at that time. Several promising

dive leads and a side passage lead still remain to be explored and mapped on

future trips.

In summing up the upstream explorations, Mike says, "Though this area will

be inaccessible to the faint of heart or those with any phobias about water,

promising leads still exist in this, Iowa's biggest and still growing cave."

|

EpilogueAfter 20

years, Coldwater Cave continues to give just enough to keep cavers coming back for more.

Wanda's Walkway carries a

significant amount of water and has entered a major ridge. The lead beyond

Grappling Falls awaits cavers with the endurance and determination to make the

trip.

The large downstream dome with the big upper level lead discovered by Steve

Barnett and Larry Fattig during an early exploration trip has never been

revisited. The upstream sumps offer virgin passage to those who enjoy the

proverbial ear crawl. In this area on the surface, the cave has almost

penetrated a ridge that extends into Minnesota and toward a large sinkhole

complex southwest of the town of Harmony.

Mike Nelson reports that beyond one of the upstream sumps, passage trends

south, a real enigma for this area of the cave where everything else seems to

be heading north.

In December of 1986, cavers used a specially modified cable ladder with a

hooking pole to gain access into an upper level fissure passage; the quest for

the upper level continues.

The promise of an upper level, an intriguing parallel drainage system and a

major extension beyond the upstream sump continue to motivate cavers today as

in the past. However, the most important factor that has been instrumental to

the work being done by the Coldwater Project is the excellent relationship

between the landowners and the cavers. Ken and Wanda Flatland understand the

significance of their cave, appreciate its beauty, and are aware and willing

to preserve it. They realize that the cave should be protected, but do not see

the need to restrict access from responsible people. Their enthusiasm toward

the cave matches that of the cavers involved, and it is with this

encouragement and support that the Coldwater Project continues. |

pppppppp

Cartography: Atkinson & Kambesis 1988 |

AcknowledgmentsIn addition to those cavers mentioned in the

article, the authors would also like to thank the following people for their

contributions to this article, the Coldwater Cave Project, or both: The

Flatland Family, Mike Bounk, Lowell Burkhead, Stacey Cyphert, Dave "Chainsaw"

Devries, Pete DeVries, Dave and Sue Ecklund, Dave Jagnow, Jim Klager, Mike

Lace, Dr. Warren Lewis, Mike Nelson, Jeff Plache, Frank Rose, Paul Scobie and

Larry Welch. So many other cavers have been involved over the years that,

unfortunately, numerous names were omitted. This does not mean that these

people are insignificant or forgotten. We salute all Coldwater cavers who have

struggled into wetsuits since the discovery, 20 years ago.